Was St. Symeon the New Theologian autistic?

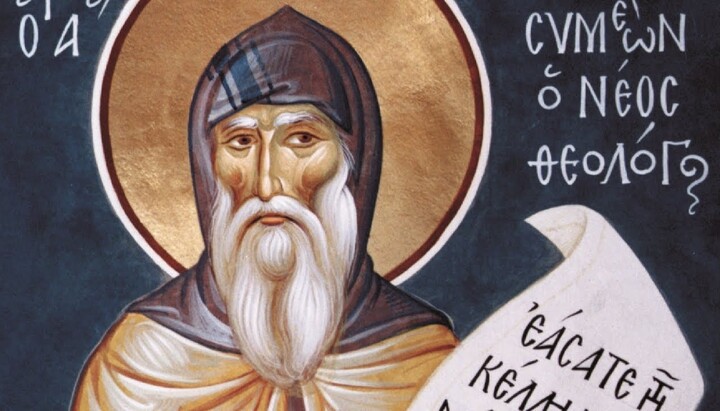

On March 25, the Church commemorates St. Symeon the New Theologian.

Although St. Symeon lived in the 10th century, reading his life makes one feel as though it's the 21st. The same debates, the same polemics. Our tragedy is that after a thousand years, we still haven’t truly heard what St. Symeon taught…

The future saint was born in 949 into a wealthy and influential family of provincial Greek aristocrats. Thanks to their wealth and connections, by the age of eleven he was living in Constantinople with his uncle, who held influence at the imperial court. Symeon received an excellent education and had equally promising career prospects. Yet, from adolescence, he began to behave in rather unusual ways. He showed no interest in a career, refused the honor of being introduced to the imperial brothers Basil and Constantine Porphyrogenitus, and generally appeared to withdraw from all the privileges showered upon him.

His official biography contains no clear explanation for such behavior. Today, doctors would likely diagnose him with a “mild form of autism.” In his own hymns, Symeon wrote of this early life:

“My parents did not show me natural love.

My brothers and friends all mocked me…

My relatives, strangers, and worldly rulers

Were even more repulsed by me, unable to bear my sight.

How many times did I long for people to love me,

And to have closeness and openness with them.”

Clearly, something about the young Symeon set him apart from his peers. They sensed his difference and, as often happens in childhood, mocked and humiliated him. It becomes easier to understand why he suffered from loneliness, a lack of friends, and an inability to find fulfillment in the comforts that wealth and nobility offered. These struggles likely led him early on to seek solace in spiritual reading, which in turn awakened his desire for a spiritual mentor – an elder. He shared his longing with others, and later would reflect on this period in his writings.

He describes hearing two prevailing opinions: true elders no longer exist – they were a thing of the past, and sanctity itself was now unattainable – times were no longer what they once were.

Keep in mind – this was the 10th century.

Later, Symeon would call those who held the second view “new heretics,” and this theme would become central to his theology.

Symeon began to pray fervently for God to send him a spirit-bearing elder – and the Lord answered. The turning point in his life was his encounter with an elderly monk who wasn’t even ordained: Symeon the Reverent. Drawing from the elder’s spiritual wisdom, the young Symeon grew in his desire to devote his entire life to God. One day, the elder gave him a book by Abba Mark the Ascetic. Three exhortations in it struck Symeon deeply and shaped his entire path:

- To live strictly in accordance with the dictates of one’s conscience.

- To keep Christ’s commandments for the sake of acquiring the grace of the Holy Spirit.

- To seek inward spiritual knowledge through prayer and contemplation.

These three “pillars” became the foundation of Symeon’s life, with special emphasis on prayer and divine contemplation. Through intense, attentive prayer, he first experienced deep contrition and tears – and soon after, his first mystical experience.

One night, during vigil, Symeon saw himself surrounded by a radiant Light. In that moment, he lost all awareness of himself – he did not know where he was, whether in this world or the next, alive or dead, in the body or outside it. When he returned to himself, it was already morning – though he had begun praying the previous evening. The night had passed like a single instant.

Despite this powerful revelation, Symeon remained in the world for many more years. He would later refer to the time between his first vision of the Light and his entering the monastery as lost and wasted. In his autobiographical hymns, he speaks harshly of himself for this delay – perhaps too harshly for some readers.

At age 27, Symeon entered the famed Studion Monastery as a novice, where his elder had also lived. From that point on, he was relentlessly persecuted by his fellow monks. His first and foremost concern in monastic life was prayer and strict asceticism. His devotion to his elder was so deep that it provoked hostility – he would not take a single step without the elder’s blessing. He revered his teacher as a saint, kissing the very ground where the elder had prayed – and did so openly, without shame, which scandalized others.

These tensions eventually forced Symeon to leave Studion.

He moved to the Monastery of Saint Mamas in Constantinople, where he was tonsured. There, Symeon received Communion daily, ate very little, spent most of his time in private prayer, and copied manuscripts as his handiwork. He wept every day while receiving Communion. Later, as abbot, he would preach the necessity of daily Communion and insist that no one should approach the chalice without tears. This again led to persecution.

From the time of his monastic tonsure until the end of his life, Symeon continued to experience visions of the Divine Light – a theme that would dominate his theological writings.

At age 31, Symeon was ordained and became abbot of the monastery. During his ordination, he once again experienced a vision of heavenly radiance. But in his sermons, he insisted that such experiences were not reserved for a select few – every Christian, he said, not only can but must see and participate in this Light. One need only seek God with all one’s heart and soul.

As abbot, Symeon not only physically restored the crumbling monastery but raised its spiritual life so high that spiritual seekers from across the empire began to flock to him. But not all monks welcomed such fervor. A faction arose against him. They disliked his open descriptions of mystical experience, could not understand his insistence on tears during Communion, and were scandalized when he preached:

- That baptism is meaningless for those who do not follow Christ afterward.

- That those who receive Communion without seeing Christ with the eyes of the soul partake to their own judgment.

- That salvation is impossible for anyone knowingly enslaved to even the smallest passion.

After one such sermon, enraged monks tried to attack him – but seeing Symeon standing serenely, face radiant and smiling, they turned instead to storming the monastery gates and ran all the way to the patriarchal residence to file complaints.

Eventually, Symeon left the monastery, hoping to live out his days in secluded prayer and contemplation. But even that was denied him.

The persecution intensified when Symeon began to venerate his late elder as a saint. He commissioned an icon of Symeon the Reverent and had services held in his honor. This led to a clash between rigid canonical formalism and living spiritual experience. Symeon saw no need to wait for official canonization – for him, his elder’s sanctity was self-evident. Yet canonically, this was a violation, and became another reason for attack.

Conflict reached its peak in a theological dispute with the powerful Metropolitan Stephen. Attempting to expose Symeon’s ignorance, Stephen posed a tricky theological question: “Do you separate the Son from the Father by thought or by action?” Symeon replied with a theological hymn – a scathing rebuke of those who live like swine yet presume to theologize like angels. Though Stephen was never named directly, everyone knew whom he meant.

The result was predictable: further accusations, slander, complaints to the Patriarch. Stephen even raided Symeon’s monastery, burned the icon of his elder, and had the saint exiled to the distant Monastery of Saint Marina near Chrysopolis.

Yet even amid these upheavals, Symeon’s mystical life never waned. He continued daily Communion and maintained his visions of the Divine Light.

His life also includes numerous accounts of miracles, clairvoyance, and prophecy. He foretold not only the date of his own death but also the solemn transfer of his relics to Constantinople thirty years later – which came to pass.

St. Symeon the New Theologian was one of the greatest theologians of the Orthodox Church and a powerful bearer of the grace of the Holy Spirit. The title “New Theologian,” first used mockingly by his enemies, became his lasting name – a title shared only with St. John the Theologian (the apostle of love) and St. Gregory the Theologian (the teacher of dogma).

His theology of divine vision and the experience of the Uncreated Light remains a summit of spiritual ascent and an example of what the human spirit can attain through prayerful life. But the high standard of spiritual life he set continues to unsettle many Christians, who find such demands excessive.

Lord Jesus Christ, through the prayers of St. Symeon the New Theologian, grant us salvation and teach us true knowledge of God.