The Orthodox clone of paganism

The time of so-called prosperity – when the Orthodox religion and the state live in peace and harmony – is, in fact, the worst time for the Church of God.

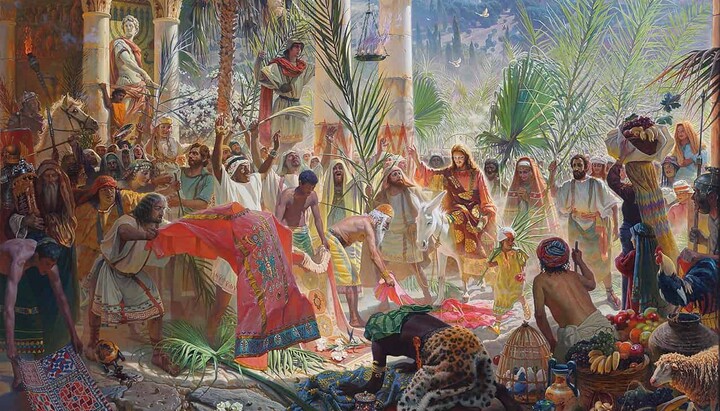

The Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem ushers in our Savior’s path to the Cross. If we look at the external social causes that led Him to crucifixion, there are two.

The first was the Jewish elite’s desire to preserve their power and comfortable way of life. Under the Roman occupiers, the leaders of Judaism lived quite well. They not only retained their authority over the people but also had immense influence over them. In the scribes’ view at the time, the Messiah was first and foremost a leader and liberator of the Jews from their oppressors. And if that were so, it would mean war – with all the ensuing consequences. It meant the collapse of a familiar, peaceful, and secure lifestyle. After the raising of Lazarus on the third day, it became clear that Jesus was no impostor. He had power and authority from above. Strangely enough, this realization led the Jews to decide to kill Christ. You’d think it would be the other way around – if He was a messenger of God, they should have supported Him. But no, they placed their personal peace and safety above the will of God. Since then, little has changed.

The second reason was also linked to how ordinary people understood Christ’s mission. They too saw Him as the Messiah – and therefore, as a leader who should lead an uprising and overthrow Roman rule. But first, we need to understand: why did they hate the occupiers so much? What was the root of this hatred?

We see that the Romans did not restrict the Jews in practicing their faith. All necessary rituals and services were conducted in the Temple. People across the land freely attended synagogues. There were already many proselytes among non-Jews. In other words, the Romans did not hinder the Jews even in their missionary work. So what was the problem? The problem was money. The only thing required of the Jews was to pay tribute to Rome on time. What they could have kept for themselves had to be handed over to the conquerors. And this sparked resentment and a desire to throw off the yoke. So again, this wasn’t about spiritual freedom – it was about economics.

But Christ entered Jerusalem not on a horse, nor with a sword in hand. He rode on a donkey, a symbol that did not represent militant Messianic ambition. And His words gave not the slightest hint of rebellion. Christ spoke of the salvation of the soul, of a Kingdom not of this world, of the need to forgive offenders and love even one’s enemies. None of this fit the image of the Messiah that the people had in mind. And so again, disappointment followed.

It is quite possible that Judas, through his betrayal, wanted to provoke Jesus into making a decisive move to overthrow Roman rule. Seeing His power, authority, and potential, Judas may have thought the Savior wouldn’t allow Himself to be killed, that He would rally the people and – with God’s help – radically change the course of history. But events unfolded very differently. And when Judas realized the terrible mistake he had made, he took his own life.

As we know from sacred history, early Christians awaited Christ’s imminent return from Heaven to Earth. They sold their houses, lands, and possessions, gave everything to the poor, and lived in a kind of commune, convinced that any moment now, the Lord would return to judge the world. The Apostle Paul supported this view, teaching: “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed – in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed” (1 Cor. 15:51–53). He believed that some might die a natural death, but others would live to see Christ’s return while still in the flesh.

But the Savior did not return, and the years went by. Persecutions against Christians intensified. Then believers decided: if Christ would not come to them, they would go to Him. More and more people sought to end their lives as martyrs. The Church began issuing admonitions, urging the faithful to restrain their zeal for martyrdom. And as the Resurrection of Christ grew further in the past – not decades, but centuries – the door was opened to something called “religion.”

History books describe this period as the triumph of Orthodoxy over Hellenism and paganism – as a victory of faith over idolatry. But this is hardly the case. In reality, even after Christianity became first a permitted and then a state religion, nothing of substance changed in the lives of the imperial court, officials, or ordinary people. Only the names of the gods and certain cult practices shifted. That situation remains largely unchanged to this day.

Those who once publicly prayed to Zeus–Jupiter now pray to Christ. Those who prayed to Venus–Aphrodite now turn to the Mother of God. The pantheon continued to evolve. Prayers for health are now directed not to Asclepius but to Panteleimon; for successful trade, not to Mercury but to Spyridon; for travelers at sea, not to Poseidon but to Nicholas the Wonderworker, and so on.

To people accustomed to living within Orthodox tradition, this viewpoint may seem strange. After all, we know that Christ is our path and the goal of our life. The Mother of God is our chief Intercessor on that path. The saints are examples of how we should live. But in reality, very few truly believe and live this way. Most of those baptized in Orthodoxy continue to practice the same paganism that existed before Christ came into the world – only with a slightly modified cult. For church-minded people, God is the meaning and purpose of life; for Orthodox pagans, He is merely a tool to solve earthly problems.

From the Edict of Milan to the present day, the Orthodox faith has existed in two forms: as the Orthodox religion and as the Orthodox Church. And often, religion is misnamed as the Church, which distorts the very essence of our faith.

The Orthodox religion, within a state, serves the same functions that paganism once did.

Its primary purpose is to fulfill the needs of the ruling power: to bless its initiatives, justify its injustices, call down heavenly help on all endeavors – good or evil. And for the common people, it satisfies what might be called a religious instinct and frightens them with God’s punishments for disobeying the authorities, since “they are established by God.”

The Orthodox Church, during the flourishing of Orthodox religion, fades into the background and lives in deep shadow, trampled underfoot by officials of both state and religion. Spiritual life takes root, living within souls that sincerely seek God and remain in ceaseless prayer. The situation changes when the state divorces the Orthodox religion and begins to persecute it. Then, those who once called themselves Christians flee from Orthodoxy as demons from incense. Only then do the true contours of the Church of Christ come into view.

Thus does God carry out an audit – of what each Local Church truly is. The time of so-called prosperity, when Orthodoxy and the state are at peace, is in fact the worst time for the Church of God. During such periods, it absorbs the poisons of this world and becomes, in essence, the antithesis of the Orthodox Church – its deep degeneration and a parody. Only in times of persecution and hardship does the Church renew itself and begin to live in hope and deep faith in God, no longer placing its trust in the powers of this world.